The legacy of methamphetamine reads like Dante’s nine circles of hell — and then some. “I am the way into the city of woe,” Dante wrote. “I am the way into eternal sorrow.” It’s a tale Warren and Barren counties in Kentucky know all too well.

Warren County ranked No. 1 in the state in meth use in 2005 and No. 3 in 2006. Neighboring Barren County, like many in Kentucky, faces the same problems. But rankings and statistics don’t begin to tell the story of a “meth.” It’s easy to get, easy to make, easy to sell and almost impossible to kick. Users forsake family and friends for another fix. Their children become an afterthought.

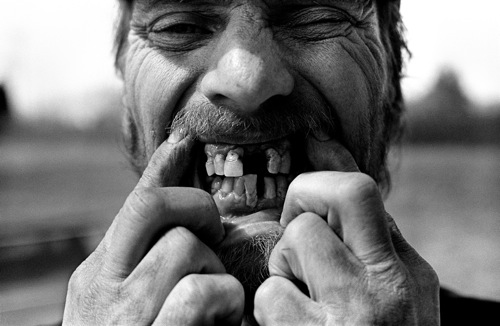

Meth destroys the body from the brain to the teeth to the fingers to the toes. Single use can lead to addiction, and drug counselors say that those who try rehab usually fail and return to the circles of hell before meth kills them or lands them in jail.

If the drug use doesn’t kill you, fires and explosions from cooking meth will or will scar you physically and mentally for life — or what’s left of it.

“I never lost consciousness, said Ricky Houchens. “I remember the whole thing. I remember the skin melting off my arms.

On Nov. 4, 2004, while Houchens cooked methamphetamine with friends, chemicals mixed with water and exploded. Houchens suffered severe third-degree burns over his arms, torso and face.

Methamphetamine found its origins in Hawaii and the West Coast, and slowly it made its way east, landing in Kentucky and surrounding states. The most potent meth now comes into the United States from Mexico via gangs. But homegrown meth remains a staple. The number of laboratories seized in Kentucky rose from 66 in 1999 to 120 in 2001 to 295 in 2005. Meth usage among teenagers also ranks significantly higher in Kentucky (12.7 percent) than the nation (9.1 percent). Part of Kentucky’s draw is its agricultural signature — rural and isolated areas, places where meth kitchens flourish. Cooking meth produces a distinct and awful smell. An